I am a firm believer in the people. If given the truth, they can be depended upon to meet any national crisis. The great point is to bring them the real facts, and beer.

– Abraham Lincoln

When the Australian Citizenship Amendment (Allegiance to Australia) Bill 2015 went through the House of Representatives, it passed without one division (or formal vote) being recorded in the official record of Parliament. This means that there is no record of how individual Members of Parliament (MPs) voted on the bill.

But aren’t all votes in Parliament recorded?

Unbelievably, they are not.

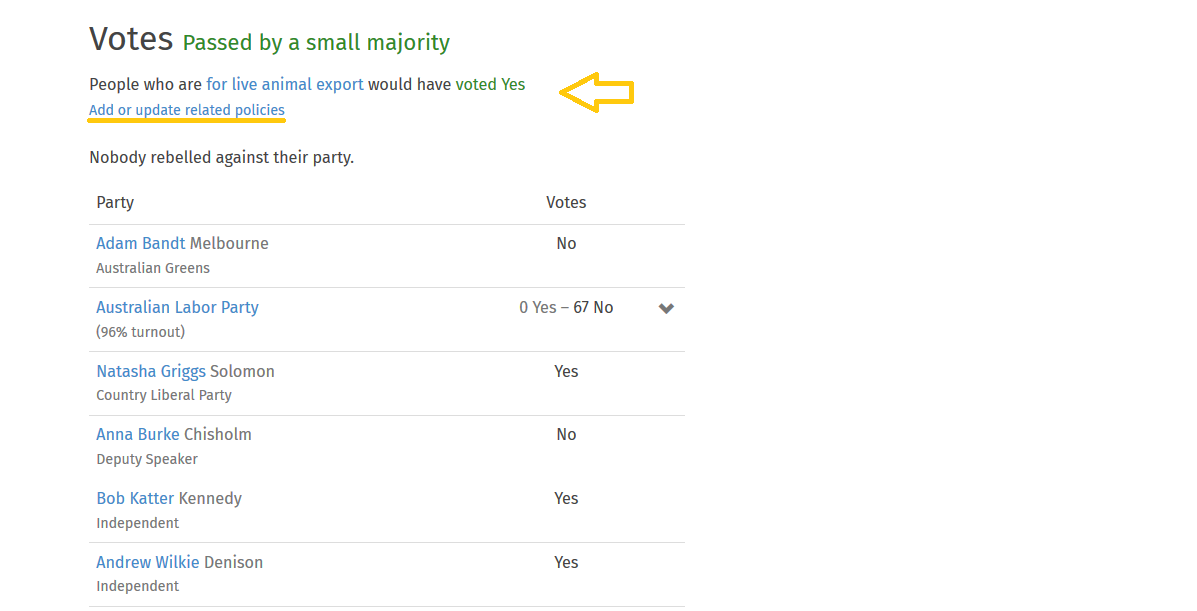

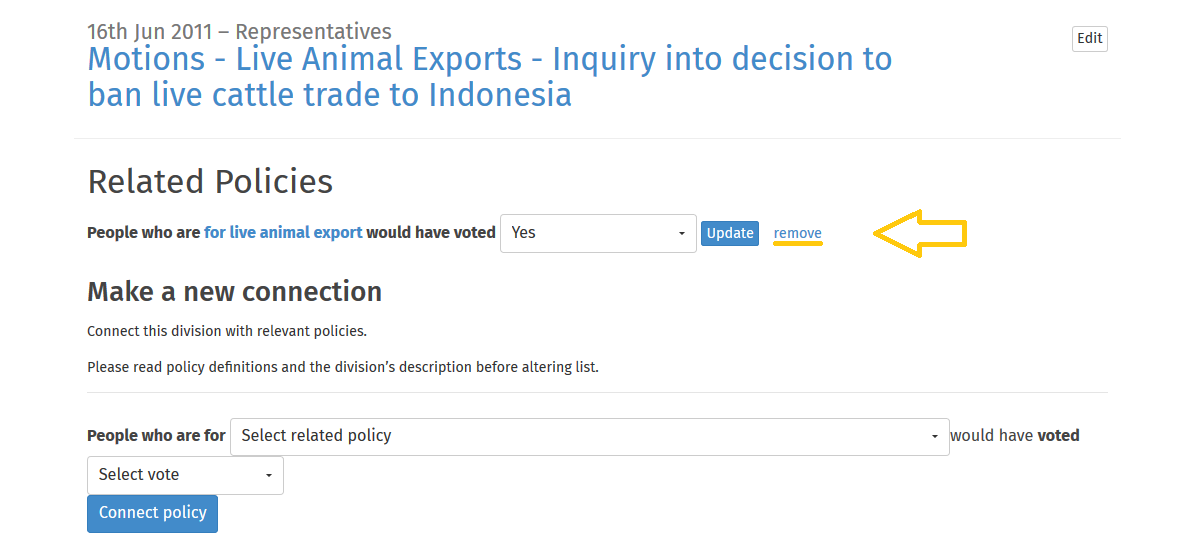

There are two kinds of votes in Parliament: votes ‘on the voices’ and divisions. Votes on the voices are the most common kind of vote and involve our representatives yelling out ‘Aye’ (yes) or ‘No’ and the chair deciding which side is in the majority without writing down any names.

Divisions are less common and only occur if two or more of our representatives call for one. When a division is called, the bells of Parliament ring out for four minutes to alert any missing representatives that they should return to their chamber immediately if they want to vote. Then the chamber (either the House of Representatives or the Senate) is locked. During a division, our representatives walk to either side of their chamber: the right side to vote yes; and the left side to vote no. Then they are counted and their names are recorded.

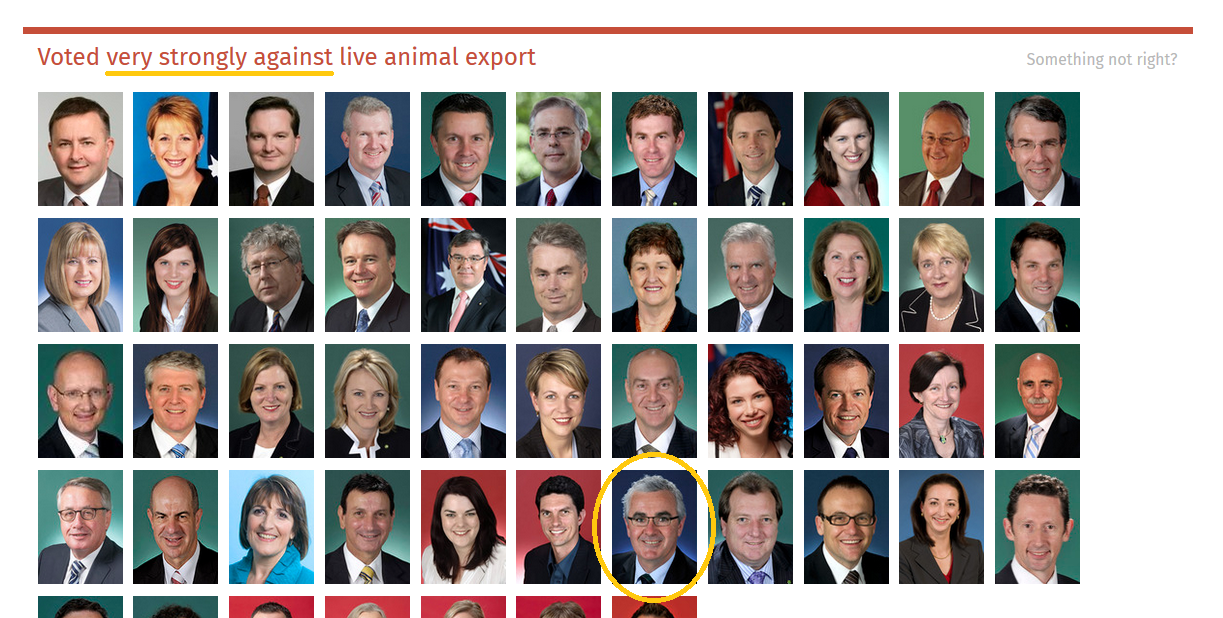

Because most votes occur ‘on the voices’, we have no practical way of knowing how our representatives vote most of the time. What we see on They Vote For You (which takes its voting data from the Parliament’s official records) represents just a fraction of the votes actually taking place in Parliament.

Why is this important?

If we don’t know how our representatives vote, we can’t hold them accountable. Bills can speed through Parliament ‘on the voices’ without any public record of how each representative actually voted. The example I mentioned above was the Australian Citizenship Amendment (Allegiance to Australia) Bill 2015 (‘Allegiance to Australia bill’), which passed in the House of Representatives without one division being recorded. This was possible for two reasons: (1) the bill had bipartisan support, meaning both the Coalition and the Australian Labor Party supported it; and (2) those major parties control the House of Representatives because almost all our representatives there (known as Members of Parliament or MPs) are members of those two parties.

On the other hand, many of our representatives in the Senate (known as senators) belong to minor parties or are independents. This means that the two major parties have far less control in the Senate and so there is more debate and a far greater chance of divisions being called, as was the case with the Allegiance to Australia bill.

In fact, most anti-terror bills have bipartisan support so that the only voting data about them on They Vote For You comes from the Senate. The consequence of this is that many of our related policies only include the voting habits of our senators, including:

- For increasing freedom of political communication;

- For increasing surveillance powers;

- For requiring a warrant to access citizens’ telecommunications records; and

- For revoking citizenship of dual nationals involved with terrorism offences by the minister.

So if we want to know how our MP voted on any of these subjects, our only option is to go to the House Hansard (the official transcript of the House of Representatives, which is also available on OpenAustralia.org) and trawl through pages and pages of parliamentary jargon and hope that our MP contributed to debate. If they didn’t, it’s unlikely we’ll ever know.

How can we make the system better?

If every vote in Parliament was made by division then we could always see how our representatives voted on our behalf. Unfortunately, this solution has a major downside: divisions take a long time. There is four minutes of bell ringing, then moving across the chamber, counting and recording, and then everyone returning to their seats. In other words, Parliament would go on forever.

There is another way however: electronic voting. Representatives can simply vote by pressing buttons on a screen, providing a complete record and saving time. It shouldn’t take any longer than voting ‘on the voices’ because representatives can stay in their seats and counting is done by computer.

The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Procedure has already done an initial investigation into the possibility of e-voting back in 2013 (see their report). While they concluded against it, they emphasised that theirs is ‘very much a preliminary examination and the Committee cannot make any considered conclusion or recommendation without details of the options and their implications’.

Their main criticism was that e-voting lessens the visibility of Members’ decision-making in the House and takes away the opportunity for Members to ‘move away from their allocated seats and speak informally to their colleagues and Ministers’. The report goes on to say that ‘[a]necdotal evidence suggests that many consider these informal professional exchanges essential to their work’.

Since there are many solutions to these objections – including the use of differently coloured lights to make our representatives’ votes visible to their colleagues in Parliament and more informal discussion opportunities during breaks – the resistance to electronic voting seems to be more about parliamentarians being sticklers for tradition. Though it is possible that parties are concerned that there may be an upsurge in party members crossing the floor (or rebelling) if electronic voting was introduced. After all, it’s easier to be a rebel when it’s just a case of pressing a button rather than having to cross a chamber in front of all your party colleagues and the gaze of your party whip (whose job includes ensuring all party members attend and vote as a team).

Calls for parliaments to use electronic voting in order to increase parliamentary accountability are growing louder. In 2012, the Declaration on Parliamentary Openness was launched and has since been endorsed by a number of organisations, including the OpenAustralia Foundation. Article 20 of the Declaration calls for parliaments to minimise voting on the voices and instead use methods such as electronic voting that leave a record of voting behaviour, which can then be used by citizens to hold their representatives accountable.

What do you think? Is it time for electronic voting in our federal Parliament?

Who comments in PlanningAlerts and how could it work better?

In our last two quarterly planning posts (see Q3 2015 and Q4 2015), we’ve talked about helping people write to their elected local councillors about planning applications through PlanningAlerts. As Matthew wrote in June, “The aim is to strengthen the connection between citizens and local councillors around one of the most important things that local government does which is planning”. We’re also trying to improve the whole commenting flow in PlanningAlerts.

I’ve been working on this new system for a while now, prototyping and iterating on the new comment options and folding improvements back into the general comment form so everybody benefits.

About a month ago I ran a survey with people who had made a comment on PlanningAlerts in the last few months. The survey went out to just over 500 people and we had 36 responders–about the same percentage turn-out as our PlanningAlerts survey at the beginning of the year (6% from 20,000). As you can see, the vast majority of PlanningAlerts users don’t currently comment.

We’ve never asked users about the commenting process before, so I was initially trying to find out some quite general things:

The responses include some clear patterns and have raised a bunch of questions to follow up with short structured interviews. I’m also going to have these people use the new form prototype. This is to weed out usability problems before we launch this new feature to some areas of PlanningAlerts.

Here are some of the observations from the survey responses:

Older people are more likely to comment in PlanningAlerts

We’re now run two surveys of PlanningAlerts users asking them roughly how old they are. The first survey was sent to all users, this recent one was just to people who had recently commented on a planning application through the site.

Compared to the first survey to all users, responders to the recent commenters survey were relatively older. There were less people in their 30s and 40s and more in their 60s and 70s. Older people may be more likely to respond to these surveys generally, but we can still see from the different results that commenters are relatively older.

Knowing this can help us better empathise with the people using PlanningAlerts and make it more usable. For example, there is currently a lot of very small, grey text on the site that is likely not noticeable or comfortable to read for people with diminished eye sight—almost everybody’s eye sight gets at least a little worse with age. Knowing that this could be an issue for lots of PlanningAlerts users makes improving the readability of text a higher priority.

There’s a good understanding that comments go to planning authorities, but not that they go to neighbours signed up to PlanningAlerts

To “Who do you think receives your comments made on PlanningAlerts?” 86% (32) of responders checked “Local council staff”. Only 35% (13) checked “Neighbours who are signed up to PlanningAlerts”. Only one person thought their comments also went to elected councillors.

There seems to be a good understanding amongst these commenters that their comments are sent to the planning authority for the application. But not that they go to other people in the area signed up to PlanningAlerts. They were also very clear that their comments did not go to elected councillors.

In the interviews I want to follow up on this are find out if people are positive or negative about their comments going to other locals. I personally think it’s an important part of PlanningAlerts that people in an area can learn about local development, local history and how to impact the planning process from their neighbours. It seems like an efficient way to share knowledge, a way to strengthen connections between people and to demonstrate how easy it is to comment. If people are negative about this then what are their concerns?

“I have no idea if the comments will be listened to or what impact they will have if any”

There’s a clear pattern in the responses that people don’t think their comments are being listened to by planning authorities. They also don’t know how they could find out if they are. One person noted this as a reason to why they don’t make more comments.

Giving people simple access to their elected local representatives, and a way to have a public exchange with them, will hopefully provide a lever to increase their impact.

“I would only comment on applications that really affect me”

There was a strong pattern of people saying they only comment on applications that will effect them or that are interesting to them:

How do people decide if an application is relevant to them? Is there a common criteria?

Why don’t you comment on more applications? “It takes too much time”

A number of people mentioned that commenting was a time consuming process, and that this prevented them from commenting on more applications:

What are people’s basic processes for commenting in PlanningAlerts? What are the most time consuming components of this? Can we save people time?

“I have only commented on applications where I have a knowledge of the property or street amenities.”

A few people mentioned that they feel you should have a certain amount of knowledge of an application or area to comment on it, and that they only comment on applications they are knowledgeable about.

How does someone become knowledgeable about application? What is the most important and useful information about applications?

Comment in private

A small number of people mentioned that they would like to be able to comment without it being made public.

Suggestions & improvements

There were a few suggestions for changes to PlanningAlerts:

Summing up PlanningAlerts

We also had a few comments that are just nice summaries of what is good about PlanningAlerts. It’s great to see that there are people who understand and can articulate what PlanningAlerts does well:

Next steps

If we want to make using PlanningAlerts a intuitive and enjoyable experience we need to understand the humans at the centre of it’s design. This is a small step to improve our understanding of the type of people who comment in PlanningAlerts, some of their concerns, and some of the barriers to commenting.

We’ve already drawn on the responses to this survey in updating wording and information surrounding the commenting process to make it better fit people’s mental model and address their concerns.

I’m now lining up interviews with a handful of the people who responded to try and answer some of the questions raised above and get to know them more. They’ll also show us how they use PlanningAlerts and test out the new comment form. This will highlight current usability problems and hopefully suggest ways to make commenting easier for everyone.

Design research is still very new to the OpenAustralia Foundation. Like all our work, we’re always open to advice and contributions to help us improve our projects. If you’re experienced in user research and want to make a contribution to our open source projects to transform democracy, please drop us a line or come down to our monthly pub meet. We’d love to hear your ideas.