You may have heard that you can now use PlanningAlerts to discuss development applications with your local councillors. With over 5,000 councillors in Australia just gathering the data is a big job. We’ve already done that for about half the councils we currently cover but we need your help to collect the rest.

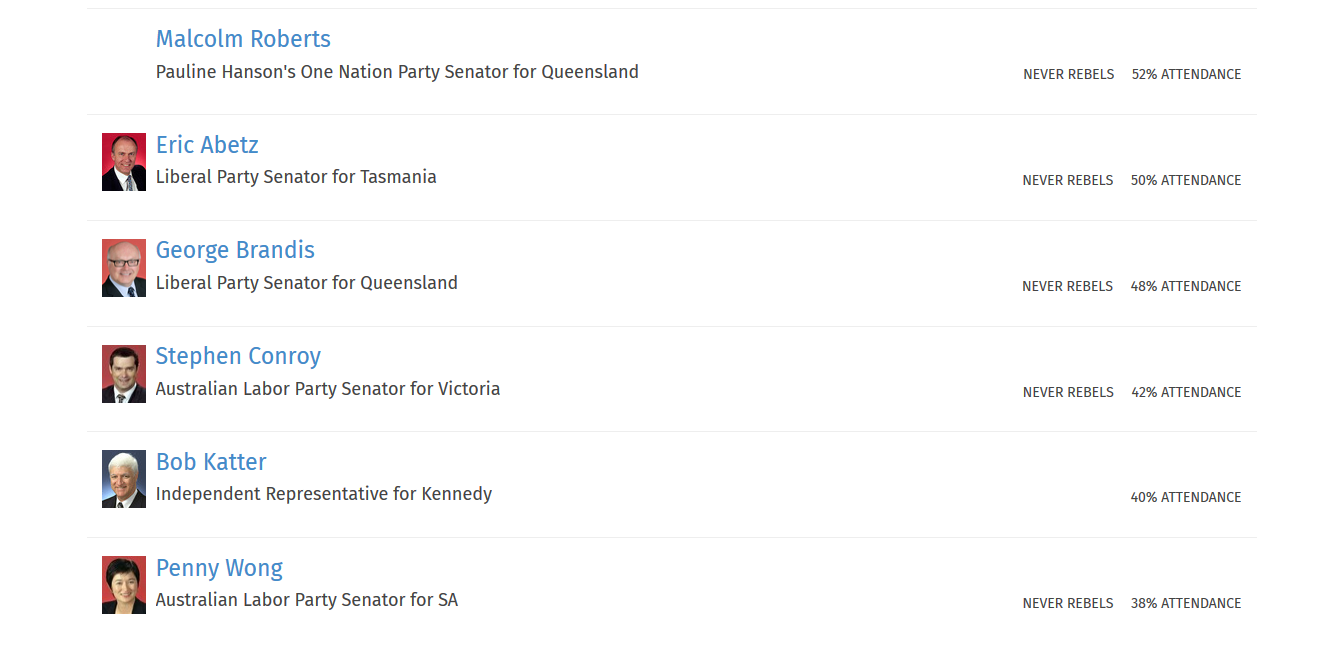

Your local councillors. If you live in Perth, that is.

How to contribute councillor information

The first time you do this you’ll need about 30 minutes. After that it usually takes about 15 minutes per council but some councils make the information very difficult to find (or don’t publish it at all!) so it’s different each time. You don’t need to be a programmer but you will need fairly good computer and internet skills (if you’re reading this, there’s a good chance you have those skills).

Find a council we don’t cover

The first step is to find a council we don’t already have data for. We’re keeping this list on a GitHub issue. On that page you’ll see a bunch of councils that don’t have ticks – those are the ones we still need data for.

Find the data and add it to the spreadsheet

All the data that powers this project is kept in a Google Sheet that anyone can edit. It’s already been pre-populated with a lot of data from scrapers (on morph.io, of course) but there’s often key details, like the councillors’ email address, that we don’t yet have. There’s a spreadsheet tab for each state so select that first, then search the spreadsheet for the name of the council you’re adding.

The next step is to find the council web page that contains all the councillor details, like this one for Perth, then copy them into the spreadsheet. Here’s a full list of the columns you can fill out. Some are essential, some are important, and some just nice-to-have. It’s important that the data is accurate so make sure you double-check it as you add it in.

Essential

name – The name of the councillor

email – Their unique email address (not a generic one for the council)

id – This is automatically generated so just leave it as is

council – This is the council name, it’s probably pre-populated

Important

image – URL to a photo of the councillor

party – The councillor’s political party. This is often available on Wikipedia but not the council’s own website.

source – URL where you got this information

Nice-to-have

ward – Councils are typically divided into wards, which does this councillor represent?

council_website – URL of the council

start_date – Date this councillor came into service

executive – Is this person a Mayor or deputy Mayor? We don’t currently display this but it could be used for other things

phone_mobile – Another field we don’t currently use but have been collecting anyway

That’s It!

Well, not quite – we’ve still got a few things to do to import it into PlanningAlerts so just shoot us an email and we’ll get started. Now you can give yourself a pat on the back…before you keep on gathering data for another council, of course ;)