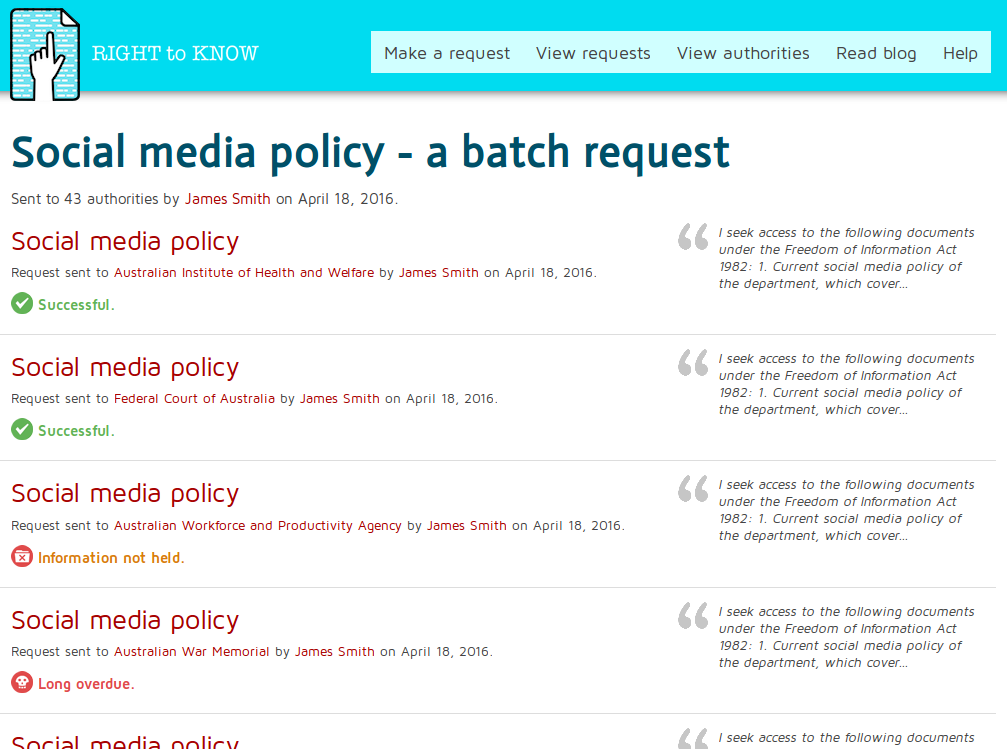

Since August 2016, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has been refusing to process the valid Freedom of Information requests they receive from people using Right To Know.

At least two of the people who have had their requests blocked have lodged complaints to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC).

One of them is Right to Know volunteer administrator Ben Fairless, who lodged his complaint in a personal capacity after the ATO blocked his information request.

On November 21 2016, the Freedom of Information Director of the OAIC’s Dispute Resolution Branch contacted us with a request for information to help their investigation into the ATO’s blocking of requests raised in the complaints. We have decided to publish those questions and our answers below.

Note that the OAIC’s questions are unlikely to have been raised by the people who made the complaints about the ATO’s actions to block their requests. Rather, they appear to be based on statements provided by the ATO that match their response to the ABC last August, that we take “no responsibility for supervising posts or removing unacceptable material”. This is false.

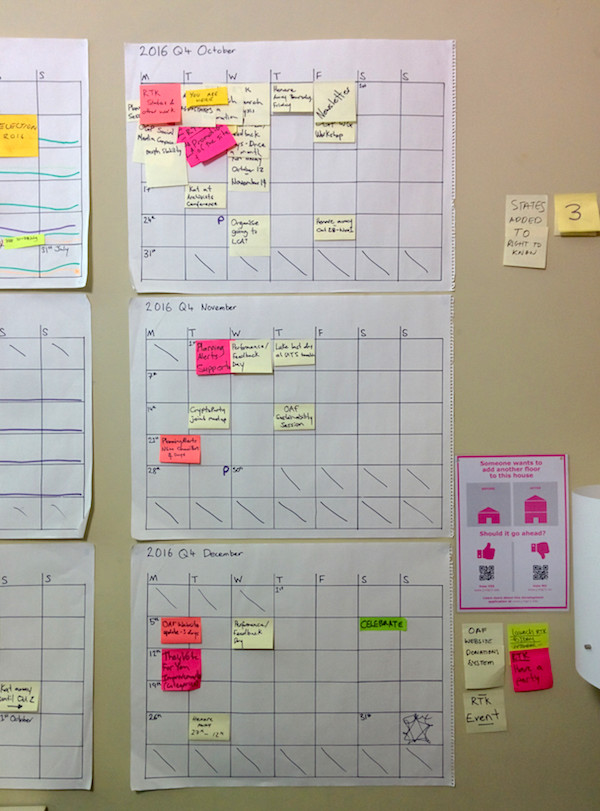

We’ve also provided a timeline below covering all communications that we have had with the ATO in 2016. We think it’s important to point out that we responded to over 70% of requests from the ATO within 24 hours. Of those, we responded to all but one in less than 1 hour. We are an independent charity and Right To Know is a largely volunteer administered project, and this record is a testament to the dedication of our community to a well run, transparent and accountable Freedom of Information system in Australia. You can compare it to the response times of all our government agencies at righttoknow.org.au.

We work hard to ensure that Right To Know is a safe environment where people can work productively with government on furthering the government’s own goals of being open and transparent. We stand by our community and join their polite and respectful calls to the ATO to start processing the valid FOI requests made to them by people using Right To Know.

Questions from the OAIC to the Right To Know Team, 21 November 2016

On November 21 2016, the Freedom of Information Director of the OAIC’s Dispute Resolution Branch contacted us with the following questions to help their investigation into the ATO’s blocking of information requests made by people through Right To Know. Here are those questions with the answers we responded with on the December 4 2016.

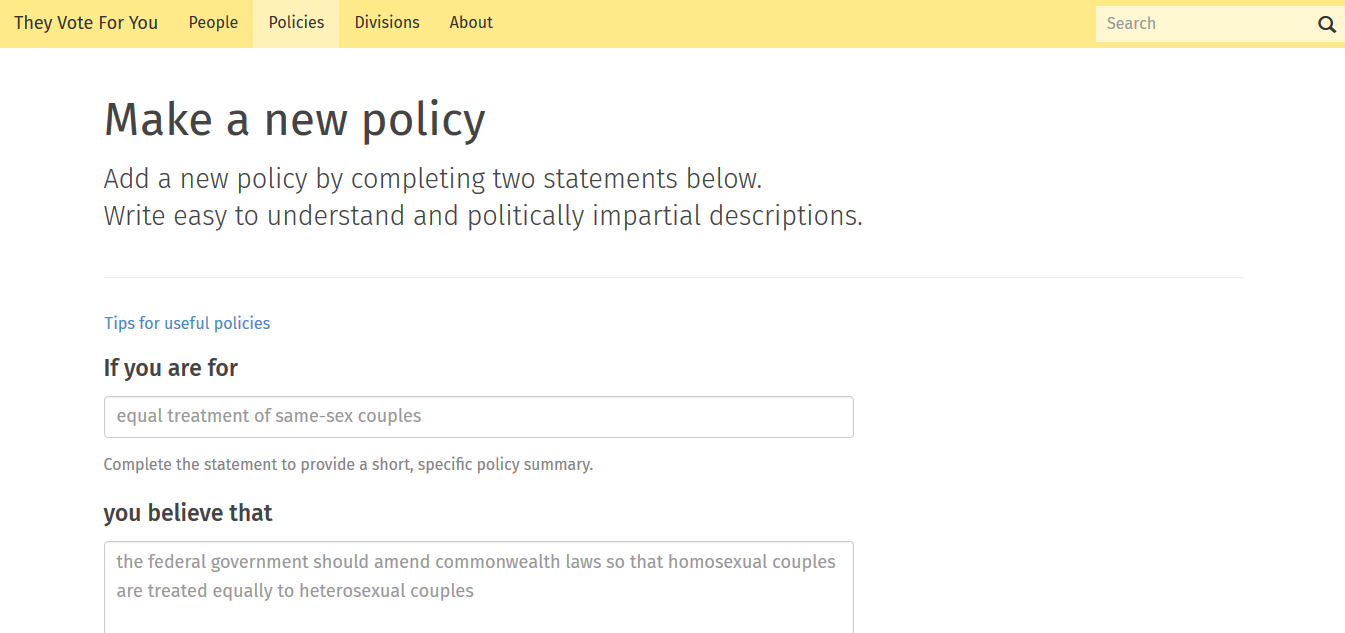

Who is legally responsible for the maintenance of the RTK website?

As is clearly stated on the The Right to Know website, the footer includes the information that the website is s project of the OpenAustralia Foundation Limited (ABN 24 138 089 942) (“OAF”) a charity registered with the ACNC and was created using Alaveteli, an Open Source software product created by MySociety. It was created by staff and volunteers. Again this information is clearly stated at righttoknow.org.au

Who is legally responsible for the publication of content on the RTK website?

Righttoknow.org.au is more akin to an open email server, rather than a traditional content publisher. We make it very clear to requesters and authorities that their correspondence is automatically be published on the internet as part of this service. Users are able to send FOI requests using the site, and agencies are able to respond to requests. In addition, users and OAF staff and volunteers are able to annotate requests. OAF staff and volunteers are able to modify content (except for attachments). OAF does not own this content

We work hard to ensure that Right To Know is a safe environment where people can work productively with government on furthering the government’s own goals of being open and transparent. We stand by our community and join their polite and respectful calls to the ATO to start processing the valid FOI requests made to them by people using righttoknow.org.au.

How are the contents of FOI requests which are submitted to government agencies through the RTK website, including all correspondence related to the request both from and to the agency, monitored?

Users register on the site and confirm they have a valid email address for the site to send them emails.

Users can then submit a limited number of requests per day. The requests are sent directly to the agency without human intervention, just like sending an email from Webmail.

OAF staff and volunteers will sometimes check requests and remove requests based on our published guidelines. For example, we don’t allow requests containing personal information or requests which are clearly not requests for information.

We rely heavily on our volunteers and others within the RTK community (including government agencies) to report requests that they feel need a second look. We take action on those requests in line with our policies, and in most cases respond the same day

How does the RTK team respond to requests from agencies or individuals for specific FOI requests or other correspondence to be taken down from the RTK website? Please provide any information on the process, timing and criteria for acceding to such requests.

All requests received via contact forms on our site are directed to a central email address (contact@righttoknow.org.au). We assess each request in line with the policies stated on our website and respond promptly.

The ATO has sent us 5 takedown requests. We give every request serious consideration and have responded to each within a day. We agreed with 4 requests and promptly acted on them to remove the material. One of the most recent requests did not meet our takedown policy so we have not taken it down.

We’ve previously been asked to redact the names of ATO staff due to a processing error made by the ATO which put their staff at risk. We responded within an hour and agreed to take down the material, giving the ATO time to supply correctly redacted documents a few days later.

In once case we were not asked to redact names. Instead we were asked to remove a request by a member of the public for an internal review into the decision about their FOI request. The ATO claimed that they found it abusive towards their staff members. The ATO’s takedown request did not meet our takedown policy, so we left the request up on Right To Know.

The ATO has responded by refusing to accept lawful requests* made via Right to Know until we comply with their demands. These include “a manned contact number, address for service, and [undertaking] to remove any unacceptable material promptly”. The ATO has already stated that they’d “probably not be successful in obtaining a court injunction to remove the offending material on the grounds it was defamatory, or threatening in a criminal sense.” (See here for the documents where this is mentioned). This appears to be a clear attempt by the ATO to impose requirements over and beyond what are required by the Freedom of Information Act, which is disappointing considering the ATO was perfectly willing to respond to several requests before our request to remove an internal review.

We work hard to ensure that Right To Know is a safe environment where people can work productively with government on furthering the government’s own goals of being open and transparent. We stand by our community and join their polite and respectful calls to the ATO to start processing the valid FOI requests made to them by people using righttoknow.org.au.

Correspondence timeline

This is a list of all contact between the ATO and Right to Know:

- 10 March 2016 – ATO request removal of 6 requests containing personal information.

- Requests were hidden on the same day as they contained personal information.

- 13 May 2016 – ATO request removal of documents that were inadvertently published which contained names of employees who deal with criminal investigations.

- Documents were hidden within 1 hour of the request being sent to our designated contact email address

- Documents were not re-sent by the ATO until 19 May 2016.

- 21 June 2016 – ATO request removal of a request containing personal and business information.

- Request was hidden in less than 10 minutes.

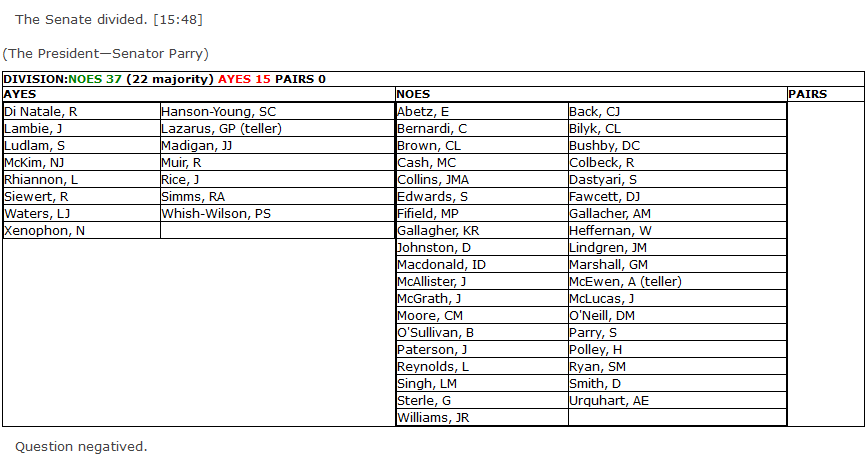

- 30 June 2016 – ATO Assistant Commissioner (General Counsel) request removal of an Internal Review request made by a person using Right To Know.

- Right to Know volunteers and staff discuss the request and determine it doesn’t meet our published guidelines for removing information from the site.

- 1 July 2016 – Right to Know volunteer calls the ATO Assistant Commissioner at his request to discuss the matter.

- Right to Know advise that it appears that the request doesn’t meet our published guidelines for removal.

- ATO advises that they believe the Internal Review request implies that staff were “untruthful and behave appallingly”. The ATO Assistant Commissioner advises they will obtain an injunction against Right to Know should Right to Know refuse to remove the request.

- The matter is referred to the directors of the OpenAustralia Foundation.

- The OpenAustralia Foundation directors decide to no longer respond to the ATO on this request and await the injunction order.

- 5 August 2016 – ATO request that Right to Know contact a user of the site in relation to the request on 21 June 2016

- 15 August 2016 – Right to Know forward the information to the user as requested

- 18 August – ATO stops responding to requests via Right to Know and advises users to contact them directly to make their request.

- 19 August 2016 – ATO Assistant Commissioner (General Counsel) sends an email about the refused requests to Right to Know

- 29 August 2016 – Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) acknowledges a review request made by a volunteer of Right to Know

- The review request was made in response to an application made using Right to Know.

- The review request was made from the volunteer’s personal email account, and it was clearly stated that the volunteer made the application in a personal capacity and not on behalf of Right to Know.

- 15 September 2016 – ATO contact Right to Know in relation to FOI requests made in relation to decision to refuse to process requests

- 16 September 2016 – Right to Know advise that we have no objection to the release of the document

- 14 October 2016 – ATO request removal of request containing a Tax File Number

- Request was hidden within 15 minutes of ATO email

- 20 October 2016 – ATO request removal of a request that contains a number of business names and ABN/ACN numbers

- Right to Know seek clarification within 30 minutes as the information is available publicly (via the ASIC register).

- No response is received by the ATO

- 2 November 2016 – OAIC contacts the Right to Know volunteer in relation to the review (now a complaint) acknowledged on 29 August 2016

- This includes a request from the ATO to remove material previously considered on 30 June

- The request is referred by the volunteer to the directors of the OpenAustralia Foundation who take no further action as they have not been contacted by the OAIC at this stage.

- 21 November 2016 – OAIC make a request for information to Right to Know (see questions and responses above)

- The directors of the OpenAustralia Foundation respond to the request on 4 December 2016

More background material

You can view peoples’ information requests to the ATO on Right To Know. In response to a request made directly through private email to the ATO, they released other relevant documents. You’ll also find correspondence between the ATO and the OAIC relating to the ATO’s actions, and peoples’ analysis of those documents, on Right To Know.