I relish elections. The political commentary, the placards, the barbeques and the jam stalls on the day. And I love election leaflets. Surprisingly still relevant artefacts of the democratic process that have maintained a unique style of kitsch for as long as I can remember. And so I got involved in OpenAustralia Foundations’ Election Leaflets, first as an enthusiastic contributor then as a volunteer Twitter moderator.

I monitored the Twitter feed looking out for tweets to promote and questions to answer, and I developed a hunch about who was contributing. Many seemed already familiar or affiliated with the OpenAustralia Foundation and I was curious about the experience of new users. I decided to investigate further and experiment with using Twitter as a source of “voice of the customer” data.

I manually screenshot 17 months of relevant tweets from 28 April 2012 through to 30 September 2013 which was just after the federal election. (Screen scrapers could only yield one week old results due to constraints of Twitter’s search API.) I then analysed this sample of 132 raw data points from approximately 70 unique profiles. The findings were positive but also revealed a break point in the experience stopping engaged Twitter followers from becoming active contributors.

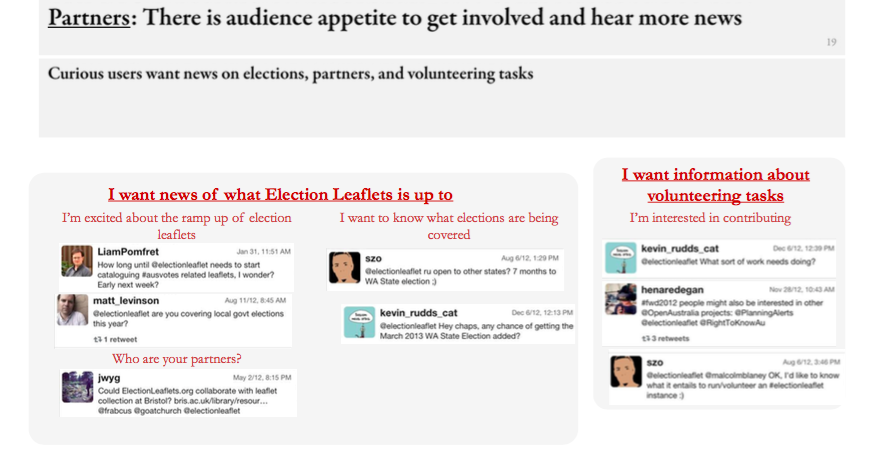

On the positive front the findings showed plenty of advocates of the OpenAustralia Foundation and Election Leaflets who encouraged others to share content, promoted the Twitter profile, were proud of their own contributions, and used the tool as it was designed – to scrutinise promotional electioneering material.

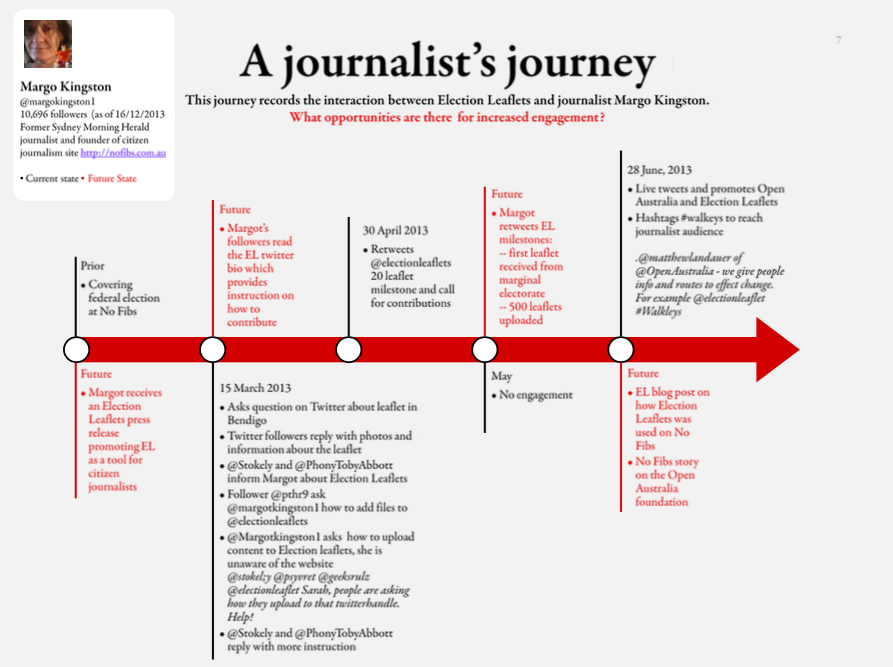

But there was evidence that despite this activity some followers could not easily work out how to contribute expecting to be able to add content directly to the Election Leaflets Twitter feed somehow. This experience was best typified by one Twitter follower, a journalist who needed to ask for help to work out how to contribute leaflets.

There were also indications that richer and more instructive experiences needed to be created for would-be volunteers to join the community and participate across all channels – from the Election Leaflets site, to Twitter, and the Google Group.

Election Leaflets had created a community of advocates and influencers but the evidence showed that it was hard for the uninitiated to contribute. The conversation and engagement that was generated by the leaflets was all on Twitter – there was nothing connecting Twitter to the site and nothing connecting the site back to Twitter to demonstrate the impact that Election Leaflets was generating.

What can we learn from this? Election Leaflets had proven itself as a successful and even fun tool. The next step for it and perhaps similar projects is to develop as an end-to-end experience. For Election Leaflets this could mean borrowing some techniques from content marketing and creating specific landing pages for new users coming to the site from Twitter outlining how it all works. It could include specific onboarding experiences for the general public and journalists. The pride and fun of people contributing could be harnessed by encouraging healthy competition and bragging rights. Further research and experiments would no doubt yield more ideas.

Election Leaflets was a minimum viable product that successfully made election ephemera easily accessible online. Its future may be at a cross roads – the National Library also archives election pamphlets although it doesn’t yet publish content live for either enjoyment or scrutiny. The next step should its evolution continue will be for us to create a minimum viable experience for both familiar and new users to meet the needs of the community as a whole.