We have made a submission to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC), who were consulting on changes they proposed to make to Part 3 — Processing and deciding FOI requests of their FOI Guidelines.

The FOI Guidelines are detail how the Information Commissioner expects authorities to handle FOI requests. We’ve shared our feedback to the OAIC below:

The OpenAustralia Foundation (OpenAustralia) would like to thank the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) for the opportunity to provide comments into planned updates to Part 3 of the FOI Guidelines: Processing and deciding on FOI requests.

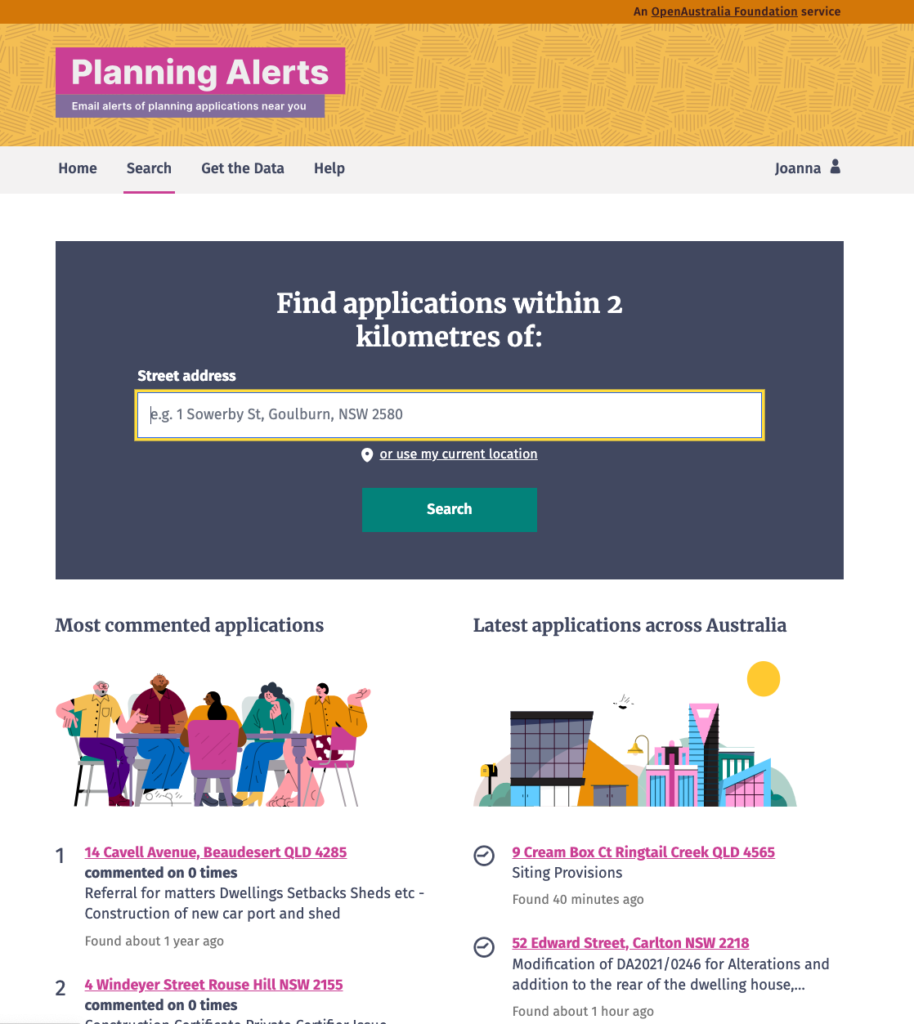

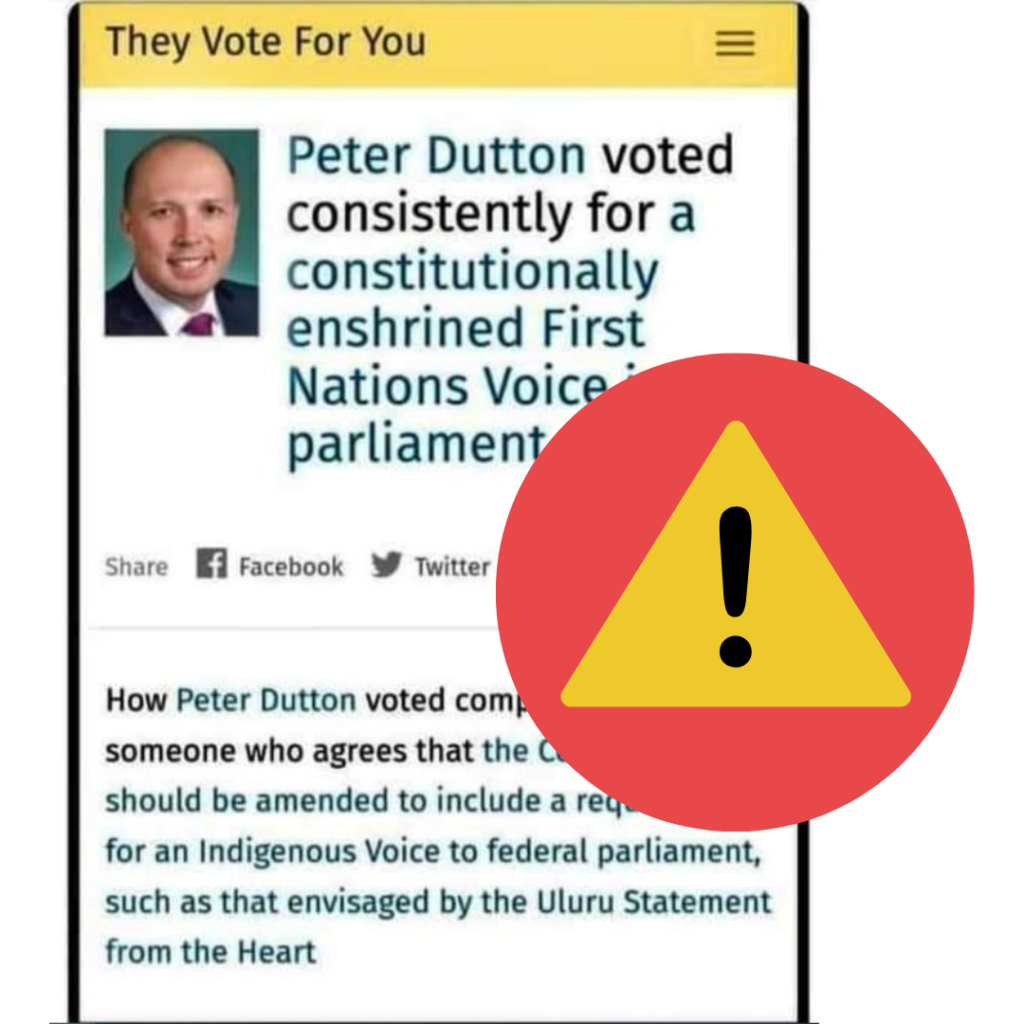

OpenAustralia is a public digital online library making government, public sector and political information freely and easily available for the benefit of all Australians. Our services also encourage and enable people to participate directly in the political process on a local, community and national level. We are strictly non-partisan, nor are we affiliated with any political party. We are simply passionate about making our democracy work.

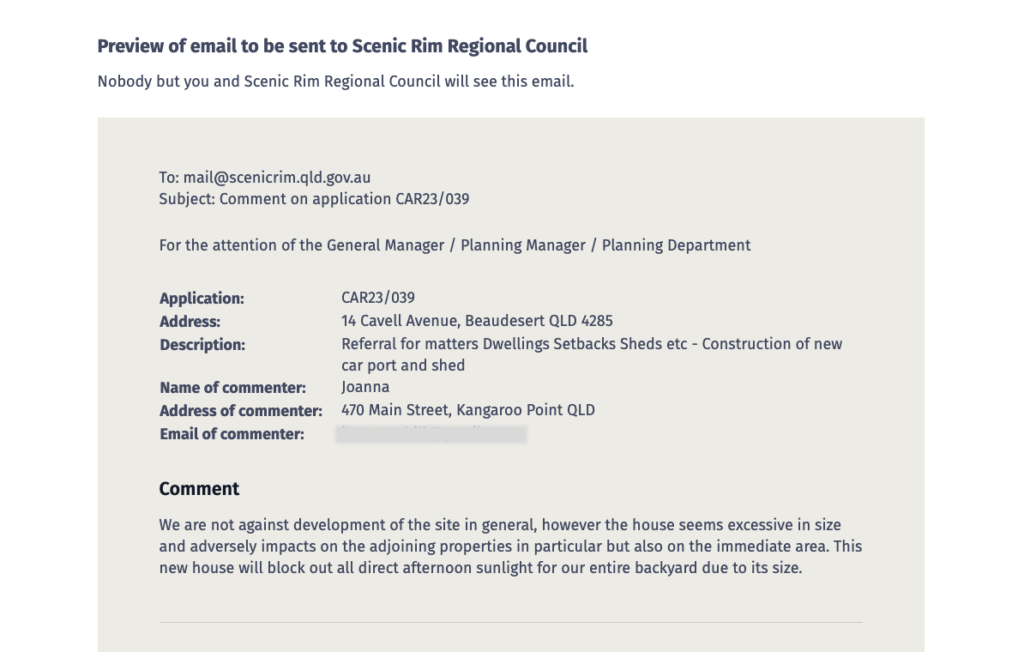

OpenAustralia hosts Right to Know, a digital library that allows people to make and find Freedom of Information requests. We bring our unique perspective over the last 14 years, having helped people make over 12,000 requests for information to Commonwealth, State and Territory governments.

We would like to acknowledge the work done by the OAIC to create the Self-Assessment tool for agencies.

Our comments are made in the context of our experience with public interest FOI requests. They are also largely confined to changes highlighted on the OAIC consultation page, due to challenges identifying changes between the current and proposed versions, which we have raised separately with the OAIC.

We appreciate the OAIC’s commitment to review better ways for stakeholders to identify, review and engage with future updates.

Processing requests for Personal vs. Non-Personal information (from the point of view of the Applicant).

Paragraph 3.16 of the FOI Guidelines makes it clear that the FOI Act does not require an applicant to prove their identity, nor does it prevent a person from using a pseudonym, unless they are requesting their own information.

The FOI Guidelines should consider clearly outlining each scenario (Personal vs. Non-Personal) distinctly and independently. They should never be conflated.

We reviewed the FOI application forms for the below agencies:

- Department of Home Affairs

- Services Australia

- Department of Defence

- Department of Health

- AUSTRAC

- Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

- Australian Taxation Office

We found that the application forms already published by these agencies request the below information:

- Full Name

- DOB

- Country of Birth / Country of Citizenship

- Phone Number

- Organisation Details including ABN

- Individual identifiers (such as CRN, TFN etc)

None of these details are required for a public interest FOI request.

In a number of cases, the wording on the website does not explain clearly (or at all) that applicants do not need to use a form to make an FOI request. An applicant unfamiliar with the FOI process could easily assume that providing this information via that form is required rather than optional.

Where an applicant is seeking non-personal information, agencies must be mindful of their privacy obligations to the applicant. Agencies have an obligation under various laws to only request the minimum information required to process a request. Agencies should proactively advise applicants that, if they are making a request for non-personal information, they can do so anonymously, and without providing any of their personal information.

There are very good reasons why applicants may not wish to provide their personal information to the government, and the reason that someone may or may not provide their personal information when making a request for non-personal information must not be considered by agencies when making decisions about their requests.

Where forms, and the systems that host them, make the default position one of requesting more of the applicant’s personal information than is needed, this does not respect the applicant’s privacy.

Easy to understand

While reviewing these guidelines we observed that the documents are difficult to understand for people who do not have a deep understanding of the FOI process.

While we acknowledge that this document is primarily aimed at FOI practitioners, applicants and members of the public need to be able to understand the guidelines to be confident that decision makers have complied with them. More work is needed to make these guidelines easily readable and understandable to a general audience.

The guidelines also refer to sample freedom of information notices on the OAIC website. We note that these notices, while helpful, contain excessive legalese which easily confuse people who are not familiar with the legal aspects of making an FOI request. They also do not seem to be optimised for use in an email. Given that these samples are intended to be used with applicants, research should be conducted with applicants to ensure that these samples are “fit for purpose”. We would be very glad to work with the OAIC separate to this consultation to help improve these.

Paragraph specific comments

We have included our comments on a number of paragraphs below.

Paragraph 3.18

Further information on the potential and current risks and problems with “artificially generated” requests is needed before a solution is included here, and should be considered separately.

Without clearly identifying the risks posed, it is unclear how encouraging the use of forms would help. What it would do is require the applicant to provide more personal information than required by law.

We are concerned there is a greater harm of agencies requesting an unreasonable amount of personal information to process a request. There is also a greater likelihood of this happening – in fact, it is already happening. This is inconsistent with s 15(2) of the FOI Act and APP 3.

Paragraph 3.29 (note 21)

There’s an opportunity to update note 21 in paragraph 3.29. Currently, this says:

The OpenAustralia Foundation Ltd, a registered charity, has developed a website (www.righttoknow.org.au) that automates the sending of FOI requests to agencies and ministers and automatically publishes all correspondence between the FOI applicant and the agency or minister. Agencies and ministers should consider whether the FOI request involves personal information or business information when dealing with public internet platforms facilitating FOI requests.

As the subject of this note, would appreciate this note being updated to something similar to the below:

The OpenAustralia Foundation Ltd, a registered charity, operates Right to Know (www.righttoknow.org.au), a service that automates the sending of public interest FOI requests to agencies and ministers. Right to Know automatically publishes all correspondence between applicants and the agency or minister. Right to Know does not allow people to make FOI requests for their own or someone else’s personal information, They encourage FOI officers to contact their team to discuss any request that may result in disclosure of personal information.

Our proposed revision reflects that our service is designed to promote the objectives of the FOI Act, and to facilitate information to the world at large. It also stresses that Right to Know, as a service, does not handle requests for personal information. We encourage anyone (including agencies) to contact our team directly to discuss any request.

We note that the former Information Commissioner has previously made it clear that requests from Right to Know are valid FOI requests. We submit that should be made clearer, given the acknowledgement from the OAIC that agencies prefer using their own online forms. Doing so may collect more personal information about the applicant than is required under the Act.

Paragraph 3.30

We reiterate and emphasise the concerns we have raised in response to paragraph 3.18 with regards to public interest requests.

Paragraph 3.32 – 3.42

We suggest taking this opportunity to amend the title of this paragraph from Assisting an applicant to Take reasonable steps to assist an applicant.

This change makes the proactive requirement for agencies to take all reasonable steps to assist applicants clearer and more accurately describes this part of the guidelines.

Paragraph 3.145 – Advising the applicant of steps required to find documents

We support the requirement for agencies to provide more detail on the steps they have taken to locate documents. For example, in this response from the Department of Defence, the decision maker provided extensive detail on the searches conducted (including search terms), the number of results, the fact that consultation was identified, the total number of hours to process and how they came to that realisation. Providing this level of detail gives applicants sufficient detail to refine their request, if they choose to do so, and provides evidence of sufficient searches in the event an applicant wishes to challenge a decision.

Paragraph 3.154

As the consultation page articulates (emphasis added), it will generally only be appropriate to delete public servants’ names and contact details as irrelevant under s 22 of the FOI Act if the FOI applicant clearly and explicitly states that they do not require that information.

While we understand that agencies may wish to give the option for the applicant to exclude staff details, agencies should not ask this question when the FOI request is submitted. Only once the documents have been identified should applicants be asked to anticipate the relevance of the material. Use of pre-emptive, leading web-form checkboxes or template requests asking applicants to consider the exclusion of public servants personal information as a condition of submission is not acceptable.

We support the agency consulting with the applicant in the event that they identify (or are likely to identify) public servants’ personal information in response to a request. It makes sense to advise the applicant what information has been found and if those details are considered relevant. For example, It may be that a name is important but direct contact details are not. In another example, the personal login details of a public servant may be the only important information in the case where a request is regarding access or changes to material..

Paragraph 3.155

Applicants should not suffer detriment (including increased charges) if an agency requests that names and contact details of public servants be removed under s.22. Further, agencies should not charge for consultation time required between employees of the agency.

Paragraph 3.160

We are supportive of the requirement for an agency or minister to mark the reasons for redaction within the document.

Applicants would benefit from a schedule of documents which detail the specific information that has been redacted, or alternatively the information redacted within the document itself. For example, instead of simply saying “s22” it might be easier to say “s22 – Staff Name” or “s22 – Phone Number”.

Agencies should be mindful that people making requests under the FOI Act may not understand the various sections of the law or how it interacts. OpenAustralia Foundation receives many queries from people seeking to understand how the law may apply to their request, or how they may ask for information. The use of legislation should be discouraged in favour of “plain english” decisions, which extends to redactions.

Paragraph 3.165 – 3.174

The guidelines should encourage agencies to make clear to applicants where a search has not been conducted for any documents that fall under section 25 of the FOI Act.

Paragraph 3.176

This guidance is incomprehensible for the general public, and even we who are somewhat familiar with the FOI process.

Paragraph 3.210

While agencies should be allowed to ask if applicants are happy to share their contact information, agencies should not be able to dictate telephone contact as a method of communication. There are several reasons for this, including accessibility (such as a person can’t use a telephone) as well as privacy concerns (such as an applicant not wanting to disclose their identity). Applicants should not be disadvantaged by a desire to use their preferred communication method.

Paragraph 3.123 – 3.214

Anecdotal evidence suggests applicants value proactive suggestions on ways that a request could be improved, such as by providing a date range or by limiting the scope of documents. Providing this information proactively supports the understanding in paragraph 3.178 (An FOI applicant may not know exactly what documents exist and may describe a class of documents).

Paragraph 3.215 – 3.216

We appreciate the legislation requires an applicant to provide written notice to the agency as part of the request consultation process. That said, agencies will be in a better position to correctly articulate any verbal agreement following a phone call.

Where an applicant is making a request via email, agencies should be encouraged to follow up verbal agreements in writing, and should accept an affirmative response from the applicant as written notice.

Alternatively, if the above is inconsistent with the law, agencies should be required to assist the applicant to modify the scope of the request after verbal agreement.

Paragraph 3.218 – 3.225

We fully support paragraph 3.223 which encourages agencies to consult applicants about release on a flexible and agreed basis.

Agencies should not seek to unfairly discriminate or disadvantage an applicant (including by charging an applicant) for the time taken to consult the applicant.

We are generally supportive of the remaining guidelines surrounding requests under s 17 of the FOI Act.

Paragraph 3.249

We support the requirement for applicants to be informed that a decision is “deemed refused” at the earliest possible opportunity. If an applicant makes a request for internal review, the agency should be required to advise the applicant of the IC review process. The agency should also advise the applicant if it intends to continue processing the request despite a decision being deemed refused.

Some applicants may not be aware that their application is “deemed refused”, and are more likely to describe the application as “delayed” or “not processed in time”.

Processing timeframes should be clearly communicated at all stages of a request, including at the start and when the timeframe has changed (for example, due to consultation). Agencies should be required to take all reasonable steps to prevent a deemed refusal, including by requesting an extension from the applicant or from the Information Commissioner.

Paragraph 3.288

We do not generally support the use of SIGBOX or other secure file sharing services for non-personal public requests for information. Applicants should not be required to provide a username and a password to a 3rd party service in order to access their documents, nor should applicants be required to access websites or file sharing services for documents or notices.

There are several risks with secure file sharing services, including the intentional or inadvertent excessive collection of personal information, as well as the security risks associated with requiring people to provide a password. Further, this is again requesting more information than the FOI requires the applicant to provide in order to make a request.